MEMORIES OF CUMBERLAND

Extract from St Aubyn's School Mag : 75the Anniversary Number (1961) edited by R. James Colley and kindly supplied by Mr Dixon, School Archivist.

Our stay in Cumberland started during August 1939 when Colonel and Mrs Colley arrived at Whitehall direct from their holiday in Scotland. The day before they arrived, one boy had come from Essex, and within a few days several more moved in. In these early days everything was rather confused; a school cannot just move into a house which has been empty for two years and expect things to work smoothly.

One thing we never really understood was the plumbing. The first time we tried out the hot water boiler, we lit it and left it to heat up for a few hours. Then someone decided to have a bath, but on turning on the hot water tap found no water. With visions of burst boilers the fire was hurriedly raked out. Not to be done out of the bath it was decided to heat water on the kitchen range and carry it up to the bathroom. When this was done it was found to be too hot so the cold tap was turned on, to produce beautifully hot water! Luckily the third tap on the bath produced cold water. For most of our stay at Whitehall doubts about what kind of water was issuing from any given tap could be resolved by the colour. Hot water came out rust red, cold water was clear, and the soft water tap produced black water.

The electric light system was equally temperamental. This consisted of a Diesel engine which charged a whole series of accumulators. When the lights started to get a bit dim, the accumulators must be getting low so the engine had to be started. If they went out completely, it usually meant that an accumulator had burst so someone had to be obtained to do repairs; in the meantime the School had to manage with candles and torches. Fuses did not seem to blow very often. One reason for this, we discovered eventually, was that the main fuse was a kitchen fork which could hardly be expected to melt in an emergency. This was the idea. At any rate by the time we left, so many storage batteries had burst that we were running on about 90 volts DC instead of the nominal 110.

Before going any further, it might be as well to mention that 'Whitehall' was originally a fortified farmhouse. A chain of fortified farms stretched right across the North of England and the peel towers were used as look-outs. The occupants were constantly on guard against Scottish marauders in search of sheep and cattle. The house was built on a slope so that it was possible to enter the cellar from the ground outside, similarly the ground floor was on ground level, and some first floor windows were only a few feet above the ground. The cellar was a massive affair which, we gather, was originally designed so that all the farm stock could be driven inside into safety. Part of the cellar formed an ideal air-raid shelter, although in fact we never had an air-raid, or for that matter a siren. Someone was meant to ring us up and tell us if there was a warning!

The peel tower on the oldest part of the house, some walls of which, incidentally, were about two yards thick, returned to its original use during the war when it was used by the Home Guard to keep a look out for enemy parachutists on moonlit nights.

Colonel Colley was, for a time, in charge of the local Home Guard Battalion, but later he decided that he could no longer spare the time so he carried on as second in command. During the first few months in Cumberland, he and Mrs Colley would be out several nights each week visiting Home Guard posts in the country districts of Cumberland; luckily Mrs Colley knew the district, or these night excursions would have become a nightmare with blacked out headlamps on the car, a district new to Colonel Colley and no sign posts as these were all taken down during the war.

Besides doing valiant service with the Home Guard, where it was nicknamed 'The Battleship', the car was an essential part of the School. Every Friday the Colonel paid a visit to Aspatria, the local village, to do the week's shopping and returned with the car loaded with Diesel oil for the electric light generator, a box of kippers, a bag of greens, shoe repairs, potatoes, medicine, wool, buttons and other necessities. Wigton also had to be visited periodically to take and collect the laundry as petrol rationing prevented the laundry bringing this regularly. On one occasion, when no other transport was available, the car was even used to take the whole cricket team for a match in Carlisle, sixteen miles away.

If this sounds as if life were rather impossible with lack of deliveries by trades people I must hasten to say that everyone who delivered anything was extremely helpful. If on the day when the grocer called we wanted some fish, or something from the iron-mongers we only had to give them a ring and they took it down to the grocers to get him to bring it out. Sometimes things were sent by bus to the post office when, if possible the postmen would bring them along, but even he was stumped one day when all the bread arrived at the post office. We had to go and collect that! Sometimes even these devious routes of communications broke down in snowstorms, and Mrs Colley would have the task of baking bread for the whole school, and just to help matters we always held on till the last minute in case the weather cleared with the result that it had to be eaten at once which caused an amazingly high consumption.

Circumstances compelled us to play Soccer instead of Rugger, but we had difficulty in raising a team on account of the small size of the School. Nevertheless, we were able to play Rickerby House, Carlisle, at both Cricket and Football and had some victories in both.

During the first year in Cumberland the Scout Troop was run by two of the senior boys, H.H. Colley and K.A. Manley, but when they left to go to their Public Schools the troop was taken over by Mrs Colley. She expected this to be a temporary measure, but twenty years later, she was still actively engaged in Troop activities. War-time restrictions obviously curtailed Scouting activities to a certain extent, but many excursions and hikes were arranged, and one or two weekend camps were held. One highlight of the war, as far as the Troop was concerned, was when a very successful display and sale of work was organised to raise funds for the Red Cross.

Some of the mistresses also ran a Cub Pack, and practically every boy in the School was either a Scout or a Cub. Unfortunately it has never been easy to organise a Cub Pack at Woodford and this has had to lapse since the war.

It is often said that camping accustoms boys to doing some of the daily chores round the house, but I think that Whitehall must have been an ideal training school for husbands. In fact, it was sometimes suggested that we should charge extra for 'Domestic Training', but on the other side of the picture we might have had to refund fees for work done by the boys.

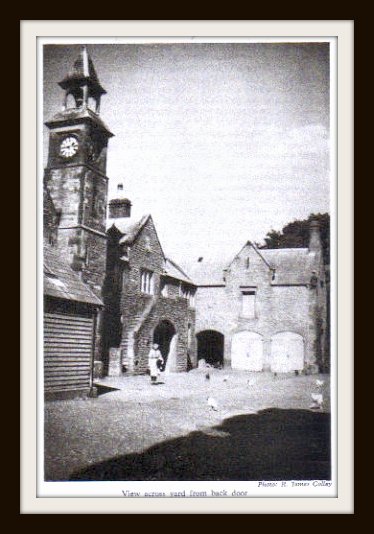

View from the back door across the yard to the Coach House

Logging was a favourite pastime on some afternoons each week, but help in the house was just as essential if the School was to be kept going. Frequently Beatrice was the only person to help Mrs Colley with the domestic work and everyone had to rally round to do what they could. Bed making, sweeping dormitories and classrooms and washing up were regular tasks for the boys. The central heating system only heated the passages and the hall so every room had to have a wood fire in it, and one of the Colonel's first tasks each morning was to go round and light the fires, but once going the boys were constantly having to bring in supplies of wood for them. At times we were able to make use of the special interests of individual boys, and for a time towards the end of the war our somewhat haphazard electric light system was kept going by one boy gifted in that way. He even kept some things going which were beyond the ingenuity of the official electrician. But somehow no one evr discovered how to stop the back door bell giving an electric shock to everyone who rang it.

Anyone going out of the back door was always greeted by a shower of hens, ducks and geese; for we managed to keep quite a flourishing poultry farm at Whitehall with the result that, if all other food failed, we could always fall back on eggs. Eventually the geese had to be given up when it was found that some of the junior day boys were afraid of going past them on the way to School, and an odd cockerel met an untimely end for the same reason. Anyone at Whitehall during the early war years will remember one hen, Maria, who kept our blackout under control. If ever she saw a speck of light showing she would peck at the window. Another of her indiosyncrasies was that she liked to lay her eggs indoors and you never knew if her next egg would turn up in a form room, on the stairs or even in a dormitory.

Perhaps she was attracted to one of the latter by the tapestried walls showing pictures of huge peacocks. It was in the old wing of the house which was reputed to be haunted although this was not admitted at the time, or boys afraid of ghosts would have been added to our many difficulties. We never really found out if there was any truth in the story, as it was not advisable to investigate rumours too fully. One thing that did come to light was that the Peacock Dormitory door was always open in the morning however carefully it was shut at night, and however carefully people were told to see that it was kept shut. Eventually it was kept open always, officially so that the staff could hear what noise the boys were making! There was also reputed to be a secret room behind a revolving fireplace and a tunnel to another farm a mile or so away. We never managed to solve the mystery of the former, although we think we found the start of the tunnel.

These 'Memories of Cumberland' could easily be carried on to fill the rest of the booklet, pages could be written about the building alone, with dry rot appearing in some of the floors, one bedroom floor parting company with the skirting board till there was a gap of several inches, and the tree trunks put up in the room below to keep the ceiling up; the minstrels' gallery in the hall, used for the projector for the film shows; the owls nesting in the peel tower, and people kept awake at night by one owl snoring on the top of the chimney; the gales and trees blown down blocking the drive.

Suffice it top conclude with words out of an earlier article. "At last V.E. Day came. We marked the occasion by a Thanksgiving Service, and after the celebrations we hoisted the School Flag on the peel tower and the Union Jack over the camp site. After this we went for a hike, taking a picnic lunch with us. We returned in time to listen to the wireless report of the surrender and celebrations and finally lit a huge bonfire when darkness had fallen." Over towards the Lake District we could see other fires burning to celebrate the end of the war in Europe. The war in the Far East ended during the summer holidays; in fact it was announced on the wireless early in the morning and Mrs Colley was on her way to Woodford on the 6 a.m. train from Leegate that same morning to take possession of St. Aubyn's. As the day went on flags were appearing on more and more houses as people woke up and heard that the war had ended. Our first load of furniture was already on the way south and soon preparations were under way for the School to follow in January.